Sanshiro Sugata is the first movie that Kurosawa directed and gained him immediate recognition as an artist. This recognition was well deserved. There is in the movie few scenes that betrays an amateur’s hand, and enough excellent scenes to be considered a great movie. Though Kurosawa quickly surpasses this movie in his own work, only movies from the short list of great directors equal it, and the only debut film which stands as tall in my mind is ‘Night of the Hunter’, the one and only movie by Charles Laughton.

Three great scenes and no bad ones is a rule of thumb for a great movie, and there are three great scenes (and more) in this one: the scene in the monastery’s pond when Sanshiro risks death to prove his dedication to the art of Judo, the scene on the temple stairs when he falls in love with the daughter of the man he must fight, and the climactic scene in the hills when he fights his opponent to the death. These scenes define the movie and showcase Kurosawa’s skill.

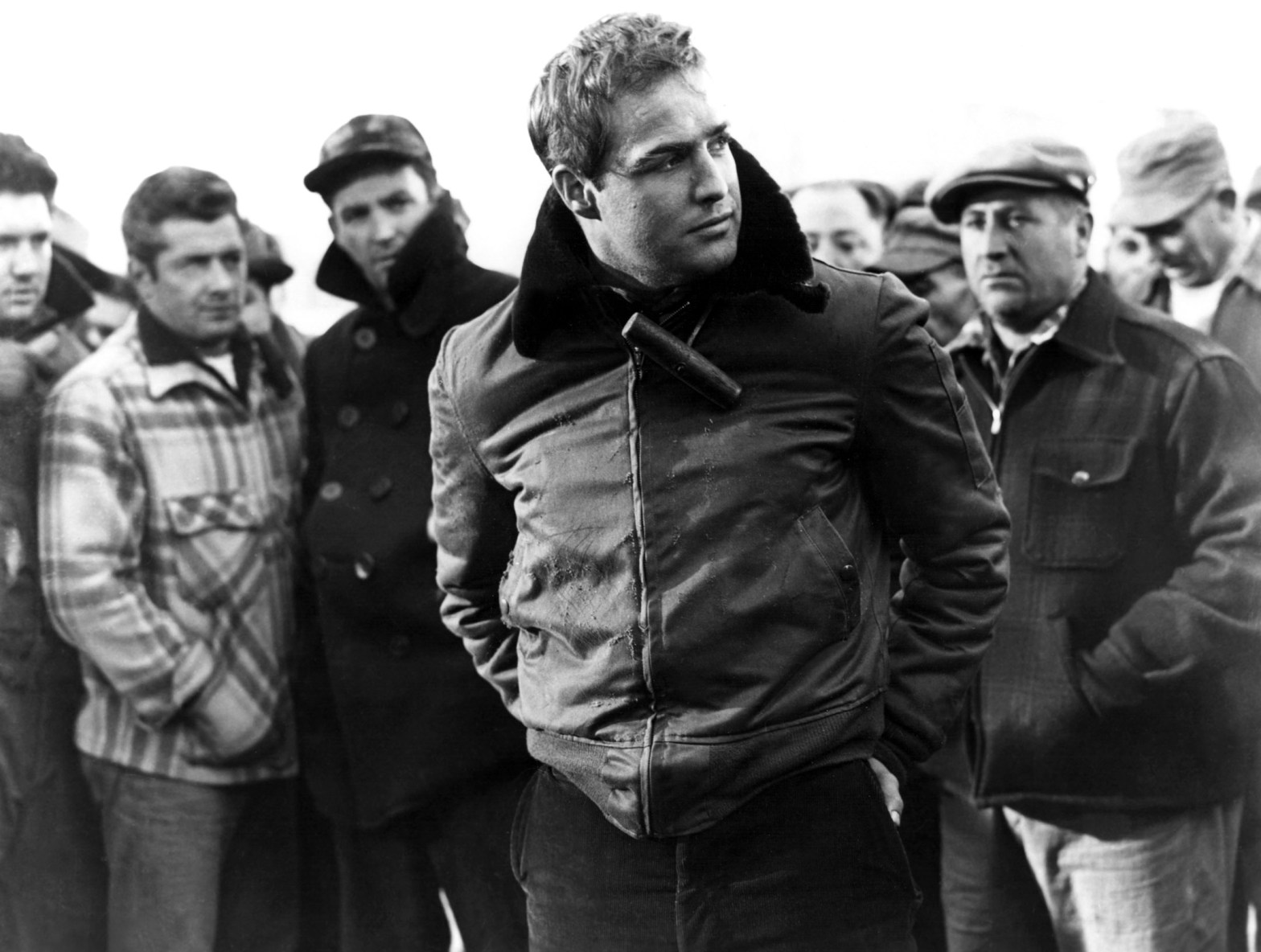

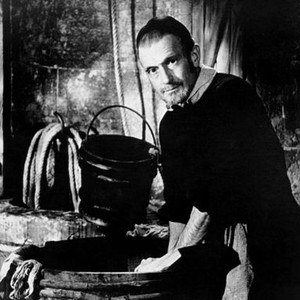

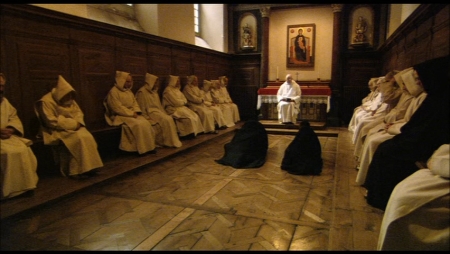

After beating up a village of jiu jitsu fighters, Sugata returns to his Judo master only to be chastised and told he does not have what it takes to master Judo. His response is surprising: desiring to show his willingness to die, he jumps out of the room and into a pond where he spends the night holding onto a post and enduring both the chill water and the jeers of the bemused monks. Somehow while in this state he is able to appreciate the beauty of a lotus flower and is immediately brought to some realization, of what is left uncertain, and springs from the water and back to his master, ready to train. This scene is more interesting for its understatement than for anything else: Sanshiro is quiet and the camera’s rhythm reflects this. The trial is interior and does not require that Sanshiro answer the monk’s jeers or silence his chattering teeth. We in fact do not see Sanshiro’s chattering teeth, we only know that he is cold because a concerned pupil is afraid he might die in the water. The detachment of the camera is the detachment of Sanshiro’s teacher, who quietly sits writing until dawn, but since at least two of the shots in this scene are from Sanshiro’s point of view, we can see that the patience of the master is forming the student.

Later on Sanshiro watches with his master as a young girl prays in the temple. In the sequence that follows he falls in love with her, and this is strongly unlined by the editing. There is a series of downward swipes, where one frame pushes the previous one off the bottom of the screen, and these swipes are seen nowhere else in the movie. In fact, these swipes are rare in editing, and so many of them so close together grab your attention. The scenes take place on the stairs descending from the temple and augment and overtake the downward motion of the couple on the stairs. This descent of the stairs portrays a peace within the girl, who has just been described as innocent, and the swipes enliven that peace without disrupting it, much as love might move the innocent. This downward peaceful motion belongs to the Japanese film language in the same way that rightward camera motion and editing belong to western film. The theory is that the drawing of the eye in the direction in which a culture reads (from top to bottom in Japan and right to left in the West) evokes a feeling of peace or rightness. In ‘The Virgin Spring’ by Bergman, the only western example that comes to mind, the young girl travels right through the woods before meeting the rapists, and left to escape them. These edits might seem technical, and perhaps you would have enjoyed the scene without seeing the stylistic tricks if I had pointed them out, but such tricks as these are what can place a movie among the greats.

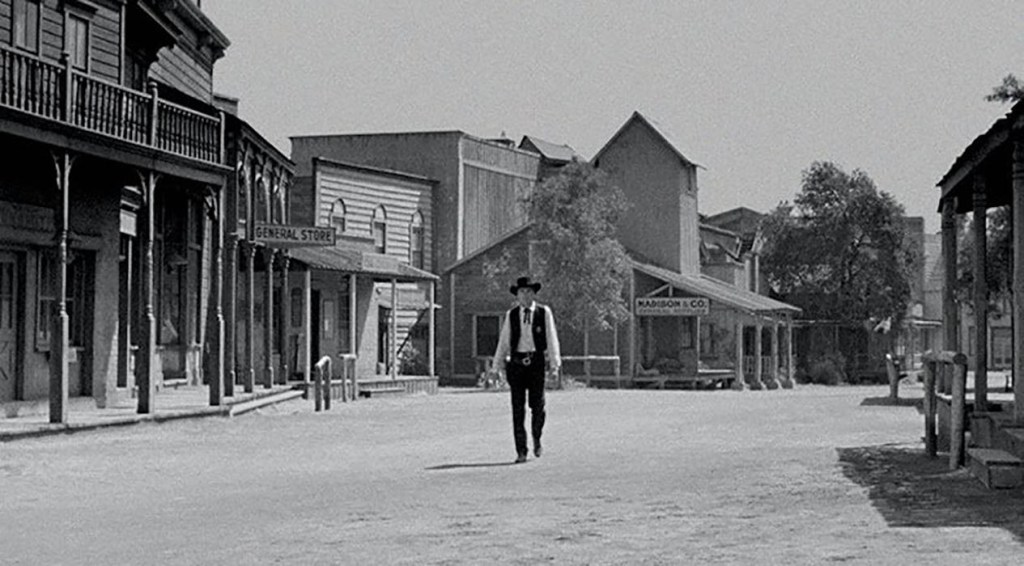

At the climax of the movie there is a fight scene, of course. This scene is perfectly laid out and immediately brings to mind Kurosawa’s later epics as well as other epics, such as ‘Samurai Rebellion’ by Kobayashi. The wind begins to pick up when the challenge is delivered and when the fighters meet in the plain, the clouds are racing overhead and the grass is shaking back and forth. Or so it does except in the shots of the antagonist. Around him there is a stillness which is at odds with the scenery around Sanshiro. With his arrive we have a shot of cloud racing straight up the screen, and again later in the fight Sanshiro sees clouds racing upward: these upward clouds work within the Japanese film language to show turmoil and perhaps doubt in Sanshiro’s mind. Until the combatants close, however, it is only Sanshiro who stands in a scene shook by violent wind. Very strange and very telling. You see, the bad guy is not much of a bad guy at all, he is just the antithesis of Sanshiro: where Sanshiro is pursuing wisdom through Judo, his opponent has rested on his laurels within the discipline of jujitsu, and the scene and its shooting spell out the greater struggle between two ways of looking at life while it shows their disciples in a fight to the death.

Look at these three scenes together: one is still with a proper stillness, a receptive one; the second is in motion but with a certain stillness that depends upon the prior acceptance of stillness: the last is of the combat between the motion from and toward stillness and that stillness which has the stillness of infertility. While his opponent has no use for beauty and believes himself justified in his stillness, even he must admit that Sanshiro has grown in skill within the story while he has not. Sanshiro’s fight does not end as we might expect, with a happy-ever-after stop, but with a continuing journey which might be seen to make an unsatisfying ending if it were not that Sanshiro is not looking for stillness, but for a peaceful motion ever forward toward a perfection unattainable in this life. He does not become a man in this movie—it is not your typical coming of age story—and he is rewarded only by his teacher saying that he is still a child. Odd, is it not?